Sunday, July 24, 2011

The Zumthor Pavilion

Another trip nicely enhanced by Facebook! When friends from Norway learned that I was going to be in London when they were, we arranged to meet at the Peter Zumthor pavilion at the Serpentine Gallery. Each year the Serpentine commissions a temporary work by a well-known architect. The last one I saw was by Frank Gehry, whose work I do admire, but that project looked like something he’d handed over to an intern (the pictures here make it look much more interesting than it actually was). Black, monolithic, and forbidding on the exterior, the Zumthor pavilion contains a nice surprise in the form of a rectangular atrium, open to the sky, with a central flower garden running its length, as well as tables and chairs for sitting and enjoying a spot of tea. It seems appropriate and much more generous for an architect to build something with a function—especially one that encourages lingering and socializing—rather than an oversize sculpture you can only walk around in and supposedly be awed by.

Wednesday, July 20, 2011

Hola!

I’m not hiding, I’m in Barcelona, where the weather is blissfully temperate, even cool, and since seeing the Àngels Ribé retrospective (1969-84) at the Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art (MACBA), I have been thinking about the current state of conceptual art. What struck me most about the Ribé show was how consciously visual the work is, offering a kind of formal satisfaction that’s lacking in similar work today. But that shouldn’t be surprising when you remember that the pioneers of conceptual art such as Ribé and her contemporaries like Vito Acconci, Hannah Wilke, Gordon Matta-Clark, and Robert Morris were extending the visual art tradition into the conceptual, whereas today the whole idea of conceptual art is so taken for granted that it becomes its own starting place, often more sociological, political and anthropological than, well, there’s no other word for it—artistic.

Ribé’s work is also varied—photographs, video, sculpture, installation—and very much about not “the body,” but specifically her body, how it—and she—relates to space and the world. There is a kind of innocence, purity and lack of self-consciousness about work that isn’t trying to prove or illustrate anything, and that clearly wasn’t made for commercial consumption. And how long has it been since we’ve seen art that was personal without being confessional?

Laberint (Labyrinth), 1969, is made of curtains of PVC, in a color and idea that eerily anticipates Olafur Eliasson.

Ribé and Fred Sandback were working with some of the same concepts at the same time. Here, in 3 points 1, 1970, there is just one line of string, while the other sides of the triangle are formed by its shadow.

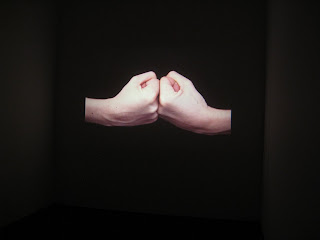

From the video Triangle, 1978.

From the video, Amagueu les nines qui passen els lladrés, 1977.

Sunday, July 3, 2011

Generation Blank: Better than alright

Jerry Saltz’s piece about the Venice Biennale (here and in a previous post), with which I agree 100%, stirred generational debate on a grand scale. Many, (like Kyle Chayka) failed to notice that Saltz's brief is with the system rather the generation itself, but Mira Schor isn't afraid to state, “I don’t trust anyone under thirty! under 40, even under 50! the farther you get from the generative decade of the 60s and yes the 70s, the worse it gets….”

Ah, the old Generation Gap, and the realization that the young ‘uns are—guess what?—NOT LIKE US. And thank God for that! Although it’s crushing to think that someone who knows what I know is out there walking around in a 25-year-old’s body, the younger people around me are generally more aware, alive, knowledgeable, commonsensical, clear-headed, conscious, emotionally astute and spiritually evolved than I was (I'll speak for myself) until just about ten minutes ago. I find I have more in common with many of my former students than a lot of people nearer my age, and often turn to them for advice.

And they should be remarkable! They were raised by US—and hit the ground running. We worked to build a world that embraced difference and diversity, and they’re living in it. Of course there’s still much to do (many, especially those who allow themselves to be brainwashed by the news media, seem to forget that the world is not, has never been, and may never be, perfect) but it’s important to acknowledge how far we’ve come. Up until the 60s there were laws against interracial marriage, yet in our family and among my sons’ circle of friends, mixed marriages are not the exception but the rule. Normal. As I’ve often said, gay marriage is an issue now not because so many people are against it, but because so many are for it. The recent sex scandals? Spitzer, Strauss-Kahn, and Schwarzenegger are men of MY generation who seem not to have noticed that times have changed and they can’t get away with that shit anymore.

And if there’s less divorce among couples of a certain demographic, it’s not because they’re suffering through marriage for the sake of the children, as many of our parents did, but because their relationships are so much more well-chosen, honest, expressed and committed. And their children? The little ones coming into the world now are observant, intelligent, and wise beyond their years. If ever you feel that the world is going to hell in a handbasket and need cheering up, just have a conversation with a five-year-old.

Maybe the personal really is the political, and these people are changing the world through the quality of their lives.

However the art—at least most of what we see in museums, galleries and coming out of art schools—SUCKS! Yet WE have been behind the institutionalization of the art world, calling the shots as it went from a “scene” to a “system.” As educators, writers, curators and art dealers, WE have decreed that art must always be young, innovative, have some kind of social agenda, and look a certain way. Could WE be responsible for this malaise? After all, WE are the choosers. WE are in charge.

Meanwhile, the music of the current 20, 30, and 40-somethings is thriving. They, too, are mining the gold that was the 60s and 70s—they did, after all, grow up listening to the Beatles—but where visual artists make denatured, watered-down versions of earlier tropes, musicians synthesize and build upon the past to create sounds that are completely theirs and of the this era.

If you listen to MGMT (led by a duo who graduated from Wesleyan in 2005), for instance, it all sounds slightly familiar and then not, and each reviewer cites a different main influence—Bowie, Eno, Pink Floyd, Joy Division and endless others. Arcade Fire’s sound never would have existed without the precedents of not just Radiohead, but Springsteen and David Byrne (who Radiohead was no doubt listening to as well).

And everyone sounds like Neil Young, except they don’t.

It's not coincidental that this flowering of music has coincided with the de-institutionalization of the music world (where WE, in the form of music company executives, were the gatekeepers), and that the institutionalization of the art world has brought stagnation.

[As Frieze’s Dan Fox asks, in a thoughtful interview with music writer Simon Reynolds, “Will the idea of constant innovation one day seem quaint?”]

Perhaps it’s time for visual art to become more substantial, developed, meaningful and mature.

But, you may ask, isn’t there a contradiction here? The music you admire is hardly “mature.” If you associate the word with age only, it may not be, but unlike the half-baked art of the same generation, it’s definitely developed. Here I take a stance based on the concepts in Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers (including the idea that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to achieve mastery) to note that while most would-be artists are just finding themselves in graduate school, generally their rock musician counterparts have been at it since they were 13 or younger, which gives them quite an edge. Not to mention that no one can match the focus of an obsessed teenager!

(including the idea that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to achieve mastery) to note that while most would-be artists are just finding themselves in graduate school, generally their rock musician counterparts have been at it since they were 13 or younger, which gives them quite an edge. Not to mention that no one can match the focus of an obsessed teenager!

Prodigies like Picasso and Basquiat ? They may simply have started earlier. [A friend who was Basquait’s kindergarten teacher at St. Ann’s in Brooklyn still has a copy of the report card where she wrote: “I just let him draw.”]

? They may simply have started earlier. [A friend who was Basquait’s kindergarten teacher at St. Ann’s in Brooklyn still has a copy of the report card where she wrote: “I just let him draw.”]

So yes, the kids are not just alright [sic], they’re impressive.

But those flip-flops they wear are ruining their feet.

MGMT’s “Siberian Breaks” (from the album "Congratulations

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)